Rachel’s Letters 1939

40 Queensborough Terrace

London WC2

September 1st, 1939

Dear Family

Still doubt and anxiety. I have just been seeing Nancy Spiers off at Euston Station. She was

lucky to get a boat home via America. The boat train was packed with Americans who are, very

wisely, getting away.

After I said goodbye to her, I tramped round London looking for somewhere to offer my

services. The Women’s Voluntary Service seemed well organised, a crowd of women were streaming

in. They had nothing to offer at present but police canteen work, which I wouldn’t mind, but I’d

rather have something medical and as they pay £2 per week, I don’t think they’ll have any trouble to

get workers. (There are hundreds of girls thrown out of work in the hotels and boarding houses,

which are practically empty.)

The Massage Association does not need people for about 3 months. Finally, I volunteered as an

assistant Civil Nurse. They are enrolling 1) fully trained nurses, 2) assistants (with some training) and

3) auxiliary nurses (who have to put in a week or so learning first-aid and home nursing). I am

waiting to hear to which hospital I shall be attached.

It is hard to get about London today as 300,000 children are being evacuated and many tubes are

not available for the general public.

Most of the banks, insurance offices and big business houses have just left a skeleton staff in their

building and have moved to the country. My bank has gone to Cobham in Surrey.

All along the street you see sandbags being filled and placed. Often the office staff in shirtsleeves is

busy shovelling. The sand-bags look pretty ineffective to me – a pile 6 or 8 feet high at the foot of a 6

storey building – but I suppose they are some use.

Windows are being covered with cellophane, or else with criss-cross strips of paper about 2 inches

wide – the idea being that if the concussion breaks the windows, they won’t be shattered and let the

gas in.

I was fitted for my gas-mask – a horrible thing! – made of rubber, with a snout filled with charcoal.

You breathe in through the snout (with difficulty), and out through the sides. We also have to carry

about various sorts of ointments for the different sorts of blister gas (in the stress of the moment I

should think one might easily use the wrong one, particularly as one has to identify them by smell –

mustard gas smells of onions and Lewisite of geraniums)

The traffic lights are all blacked out, leaving just a tiny cross in the middle to indicate the colour –

you have to watch it very carefully.

Cars stream by in hundreds, bound for the country, loaded up with suitcases, cats, canaries etc, and

often you can see a car full of office desks, files, business papers etc.

All the city hospitals are being evacuated today to be used as casualty stations. The patients have

been sent to the country in Green Buses.

The balloon barrage, which is supposed to protect London is being prepared and several balloons

were lying on the ground in Hyde Park this afternoon, looking like enormous silver slugs. They are

Rachel’s Letters 1939

sausage shaped with a 3-winged tail. They float high over the city, attached to the ground by very

strong cables, and, I believe, electrified nets stretch from one to the other.

Every house has to have an air-raid shelter in the garden or, in these old London houses, a room in

the basement for the purpose. Buckets of sand and water are kept in different parts of the house to

put out incendiary bombs.

The windows have to have absolutely light-proof curtain and most of the lights have to be shaded as

well, lest the opening of a door should throw a beam of light outside.

No torches are allowed in the street, which is a great hardship. Tonight, was the first real black-out. I

went to Notting Hill Gate to see a girl while it was still daylight and came out into pitch black and

drizzling rain. It was really horrible – I stumbled along, bumping into people and hanging onto my

purse hard, and every second step seemed to be a curb. The cars and busses only use their parking

lights and those are covered with paper. You can’t see the number on the buses. They loom out of

the dark and whizz by in an alarming fashion. It is most eerie. The Underground Stations have all

their light painted blue, and that gives a weird effect, but they’re more cheerful than the streets.

The people are wonderfully calm and steady, and usually cheerful. The organisation seems splendid.

The A.R.P. have air-wardens in practically every street. They wear tin helmets and a khaki rubber suit

in action, and their job is to warn people and deal with air-raid emergencies.

The Auxiliary Fire Service, both men and women, wear tin helmets and black suits with red letters.

They seem to be in readiness everywhere, with hoses and ladders in private cars and trailers with

hoses are ready to be hooked onto 3000 volunteer taxis.

Of course, they’ve had a long time to get ready, but they really seem to be ready for anything and

their spirit is great.

Everyone hopes that some 11th hour miracle will save the situation, but it couldn’t look much worse.

Sept 3rd

Well the blow has fallen. I listened in at 11:15 this morning and heard Mr Chamberlain’s speech.

Poor man, he must be heart-broken after all his efforts. Well we’re in for it now! I eagerly grasp at

every rumour that Germany is falling to bits, but I don’t suppose it’s true.

At 11:30. Just after we had heard the news, an air-raid warning was given – wailing sirens and

intermittent blasts on hooters and whistles. The air-raid wardens dashed up and down the street

shouting “take cover”. We grabbed our gas masks and ran down to the basement, with a horrible

sinking feeling in the pit of the stomach – at least I had -I don’t know about the others. They were all

quite cheerful. The cook was inclined to be hysterical until something on the stove boiled over and

aroused her to her responsibilities. However, nothing whatever happened. In about half an hour the

“all clear” signal blew (a long-sustained blast on the sirens). We heard afterwards it was a strange

plane sighted on the south coast, which turned out to be a friendly one.

I wish I had some idea how long it would be before I’m called up, as if it would be long, I would move

to where I know someone, or to an ordinary boarding house. I find this a bit grim at a time like this

by myself. Doris is somewhere in Scotland and everyone seems to have scattered. Anyway, you can’t

use the telephone for private calls, and it is hard to find people. I was talking to Helen Taylor today –

she’s at a hospital doing tests for blood transfusions. I also found Ethel Stukey yesterday, living quite

near and sharing a flat with Miss Harrison, who knows Thea and went to England on the same boat

as Howard.

This afternoon I went for a walk in Hyde Park and felt quite cheered up. Everyone looked quite

cheerful and very few were bothering to carry their gas-masks (which they should do). The scene

was just like any Sunday afternoon in the park, except for a few uniforms and tin helmets, and the

balloons overhead.

Well, good-night, my dears

Much love to you all

Rachel

Sept 4th, 5am

I was in a lovely sleep at 3am when the sirens started – I had put everything ready, and in a few

minutes, everyone had collected in the basement, all yawning sleepily. We had to put the lights out

and it was pitch black but for a few cigarettes glowing. Everyone was cheerful and some of them

amusing. After a while, with the aid of a torch, someone made tea. There are about 20 in the house

including the staff.

Again nothing happened, and in about three quarters of an hour we came back to bed, but not to

sleep, as planes (evidently our own) flew ceaselessly overhead, search lights flashed and one was

listening all the time for the sirens. I suppose in time we’ll get used to sleeping with one ear open.

I tried to get hold of Mrs Bevan, but she has gone to the country. So has Betty with her charges – at

least she’s left London – she may have left for home.

It is cloudy this morning and I can only see a couple of balloons – yesterday I counted 119 from my

window. I don’t understand how they work, after hearing the home planes last night – probably they

were further away than they sounded.

They evidently give the alarm when enemy planes are sighted off the coast, and it doesn’t mean

they are near London

Rachel’s Letters 1939

17 Edward Street

Bath

Sept 15th, 1939

Dear Family

Well the war goes on quietly for us, though not so quietly, I fear, for the poor Poles.

I am dying to get your next lot of letters. The last ones were August 25th. The next mail we are told

has been delayed. I hope it hasn’t been lost.

I am still down in Bath, leading a quiet life. I don’t think I am likely to be called up for nursing until

there are civilian casualties and so far, I haven’t landed any massage job. They told me there

wouldn’t be any for some months. So, I don’t see any point in rushing about feverishly doing

unnecessary jobs, so I am having a good rest.

Betty Joske and her charges are still here, and we go for walks and short expeditions into the

country. Betty is waiting to hear from their parents what they want her to do, as she won’t take the

responsibility of deciding by which route they should sail. Old Mrs Stratton from the Goonawarra is

also here waiting for a boat.

I went up to London for 3 days last week to do some business and say goodbye to Doris Marsh, who

has gone home in the “Empire Star”. A hazardous business, but I think it best to risk the submarines

and get away if possible if one has something definite to do there.

London is a great deal emptier than it was a fortnight ago. Over a million (I think that’s correct)

children and mothers with small babies have been evacuated to the country. People have flocked

away from the hotels and boarding houses, and many hotels are facing bankruptcy and others have

just had to close down.

Nobody goes out after dark in London (or anywhere else) if they can avoid it. You are not allowed to

use a torch, and it is awful stumbling along, bumping into people, tripping over kerbs, getting lost,

and falling over the heaps of sandbags which are all over the pavement. There is talk of lifting the

blackout a little, allowing shaded torches and more lights on cars, as there have been so many

accidents. The pedestrians can see the cars but can’t judge their speed and the cars can see nothing

but a bit of dimly lighted road about a yard in front of them. It is the same all over England – the

villages and country houses have the same restrictions.

All places of amusement have been closed since the outbreak, but pictures are opening this week in

the daytime and early evening. When I was up in London, Helen Taylor and I went to the re-opening

performance of “The Importance of being Ernest” at 7pm in an outlying suburb. It was done by John

Gielgud and a first-class company and was splendid. I have never heard such an appreciative

audience, all enjoying being able to do something cheerful in the evening. Getting home was a bit

difficult. The tubes are very contrary, as 20 underground stations have been closed, and you have to

go round in circles to get anywhere. They are afraid of them being flooded if the Thames are shelled

and are building protective walls of some sort. Some will be opened when they are ready, but others

will be closed for the duration.

Bath is very full – hundreds of mothers and children and now the Admiralty (or part of it) are moving

down. The four largest hotels have been commandeered and 7000 clerks and typists are billeted

among the people. It is a great hardship to many; though willing, they don’t know how to cope with

it. Poor old cousins Cha and Jessie, both frail, have four. Preparing the rooms nearly killed them, and

Rachel’s Letters 1939

as soon as the girls arrived the maids gave notice. They have persuaded them to stay on, but I don’t

know for how long. They won’t let me do anything to help them – they are too agitated to know

what they want. The same thing is happening in hundreds of houses – the staff walking out and

leaving poor old people in an awful predicament.

We hear many tales too, of the hardships entailed in having discontented mothers with many

babies, who long for the cosy little pub on the corner; and older children, very wild, verminous and

with very dirty habits, billeted in nice houses. Many of them just can’t stand the quietness of the

country and are drifting back to London. However, there are many thousands of them very happily

situated, and it was a big achievement getting them all safely away, and it will be a wonderful thing

for their health. I saw a larger batch of them today in a little village, looking very rosy and happy.

Cousin Jean Fowler has 3 schoolteachers billeted with her, and the children are in cottages in the

village. Cousin Jean is just the same with her gruff, happy-go-lucky manner. She enjoys having the

teachers there. I went to lunch there last week. I thought Gastard House looked much smaller and

she tells me she pulled half of it down, as it had dry rot in it, and it was too big for her anyway. It is a

cold barn of a house even now.

I went to Bristol to see Helen Gawne last week. They are a delightful family and Mary a charming and

interesting child. Helen is very crippled, but can get about a little, and is wonderfully cheerful. They

have a very nice BBC musician billeted in the flat. Most of the BBC are in Bristol. Government offices

are scattered all over the country. A thousand hotels in the provinces have been commandeered in

the last few weeks. The cost of it all just makes one gasp, and it’s only beginning.

I have been to see Cousins Hereward and Julie Roberts. They have left their house and moved into a

flat lately. C Hereward looks well and much the same as when I saw him last. Cousin Julie, I thought,

looked rather frail. Llewyn and Joan are staying with them; she is an awfully nice girl. Llewyn has had

hard luck; he has apparently been overworking with no decent holidays for some years, and a few

months ago had a bit of a nervous breakdown, and decided to retire from the army, and, as soon as

he felt fit, to look for another job. He remained on the Reserve, however, and now this has come,

has to go back inti it again as soon as he is well enough. It doesn’t give him much chance of getting

really strong again, as no one can rest with an easy mind just now. He says he is much better,

though, and looks well but has been sleeping badly.

Curtain rings and drawing-pins are precious as gold in England, and very hard to obtain, since this

business of covering all the windows. It is quite a job to make them completely light-proof. I met a

woman who works in a large institution with almost 1000 large windows and she told me it was

costing £1 each to darken them. €1000 for one building!

There is no shortage of food, but ration cards are to be introduced soon to ensure control and an

even distribution.

Everything seem to be well in hand. The various organisations are really wonderful.

The London hospitals have all been evacuated and prepared for the reception of 300,000 civilian

casualties (incidentally the staff are getting very restless with nothing to do).

The Auxiliary Fire Brigade, together with regular Fire Brigade, is ready to deal with 30,000

simultaneous outbreaks of fire.

You will be tired of all the statistics, but it is the only way to give you any idea of what is being done.

Rachel’s Letters 1939

The London shops are all open as usual. Their windows are all covered with strips of paper in various

designs. You can do them horizonal/vertical or diagonal mesh, or if you are enterprising you can

arrange them to form pictures.

The mudguards of all cars, even the most sumptuous Rolls Royces have to be daubed with white

paint, and steps and kerbs painted white too. Oh, and believe it or not, the ponies in the New Forest

have been painted with white stripes so that the motorists have a chance of seeing them!

I had a letter from Mrs Young some months ago, saying that she was bringing Marjorie over to be

married to an Englishman in August, and was herself staying about 2 months before returning. She

gave me no address though – just said she’d get in touch with me when she arrived so I can’t trace

her.

We have been very lucky with the weather, which has been perfect all September, and has helped to

keep our spirits up. I expect it must break before long.

Much love to you all,

Rachel

Rachel’s Letters 1939

Bath

October 5th, 1939

Dear Family,

The War still pursues its peaceful course – at any rate in Bath! But for the unwonted number of

people about, and the hundreds of Naval uniforms, you would never know there was anything

wrong here.

Betty, the Evans girls and Miss Stratton are still here but they have today taken their passages on the

‘Orana’ for Oct 21st. I shall miss them dreadfully when they go, it has made all the difference having

them here.

Mrs Bevan and Hilary left last week. I exchanged letters with them but never managed to see them.

There is not much travelling about England now – the trains are very few and far between and stop

at every station and are of course very crowded. After dark, the only light allowed is one tiny blue

bulb, by which you can just distinguish where people are and that’s all,

I hope the Bevans get home safely. They seemed to enjoy all they saw, though, of course, their trip

was very curtailed. Mrs B must have kept reasonably well, I think – she wrote very cheerfully and

said it had been worth coming.

I have just spent a week in Wellington, visiting the Fox relations. I suggested a day’s visit to Cousin

Anna (one can’t expect to stay with anyone now as all spare rooms are full), however she arranged

for me to go to her nephew’s house, where they had a spare bed for the moment. Cousin Anna has 7

evacuees and Cousin Agnes 15. I had a very happy week there, they are such a nice crowd. They

were extraordinarily kind to me, particularly when you realise that the relationship is so distant as to

generations back! Of course, they wanted to hear about Cousin Bob and Mary, whom I had seen just

before I left.

There are 6 or 8 different families, all living in lovely homes. Not pretentious but large, comfortable

houses all in perfect taste and with beautiful gardens and lovely vistas over the surrounding fields

and hills.

The atmosphere of Wellington is rather feudal. The little town seemed to consist almost entirely of

Fox homes, the Woollen Manufacturing Works and the workmen’s cottages connected therewith.

There is a strong Quaker strain still in the Fox’s. They abound in good works, but they are not dull.

Several of the younger ones have married artistic women which accounts for their attractive houses.

One of the younger ones, Sylvan, has got religion badly, become a British Israelite and discourses in

Hyde Park! I must go and hear him sometime! In the house where I was staying, they have adopted 2

little German Jewesses, 12 and 9. At least they hope to be able to return them to their parents

sometime, but they haven’t heard anything of them for some time and have grave doubts about

them being alive.

Petrol is now rationed. The amount varies in different cases, according to the make of car etc, but it

averages about 7 gallons a month for which you have the coupons. You can’t store it; it must be used

in the month for which you have the coupons. It is difficult for people living a few miles from a town

and having to go in daily for business or taking children to school. The motor transport businesses

are very hard hit. I expect they will have to make special terms for them.

Gas, electricity and coal are cut down to 75% of last year’s allowance.

Rachel’s Letters 1939

On Friday, a national register census was taken, and now we all have an identity card, which will be

used later for food rationing. The register is also to enable them to access the man (woman) power

so that no energy will be wasted.

People are rather overwhelmed, though not altogether surprised by the 7/6 in the £ income tax.

Things have been so quiet that there is beginning to be a bit of a reaction against all the stringent

regulations and restrictions. Theatres and pictures are opening again in London and the blackout is, I

believe, being lifted a little bit there.

Hundreds of evacuated children are drifting back to London and are causing difficulties as there are

no schools for them there now.

The mothers with young children are also getting restless and beginning to go back. One can imagine

how they feel in unfamiliar surroundings, away from their homes and husbands, and with nothing to

keep them occupied. In some cases, they are dreadful creatures – Limehouse opium smokers and

such like, but in most cases, they are reasonably decent working people trying to be grateful but

very miserable. If they go back, they can’t, of course, be evacuated again and this ominous calm is

not likely to last indefinitely. It is a difficult problem.

In the villages, the residents are doing a wonderful lot of social work among them, trying to smooth

over difficulties between the billeters and billetees and looking after their health and providing them

with recreation etc. In thousand of cases the children are mostly situated in cottages where they are

very welcome, and I am sure it will be of lasting benefit to them. They are mostly poor little whitefaced, skinny creatures, and they look blissfully happy fishing in the streams and gambolling about

the fields.

Another problem is the ARP staffs. Thousands of them are being paid £3 a week, and have nothing to

do but sit at the end of telephones waiting for air alarms. And yet they may be needed desperately

at any minute.

On Oct 9th I am going to Bude for 10 days to look after Susie Mack’s family while she goes to

Portsmouth to be near Arthur for a little while. She is afraid he may have to go to sea soon, and she

is straining at the leash having to stay in a safe place with the children. They have taken this cottage

in Cornwall until Xmas.

Yesterday I heard that I am allocated to a hospital in Bedfordshire as an assistant nurse. The Three

Counties Hospital, Arlesley. I have not to go yet, but to hold myself in readiness to go when called

up. Lots of people forecast the middle of October as the time when things will begin to happen, but

of course no one knows anything. Of course, I shall only be doing this work until can get my own but

that will be later on.

No one knows what to make of Russia’s joining up with Germany – whether it will prove the rope by

which Hitler eventually hangs himself, or whether together they are going to prove an irresistible

force. It is a grim sight to see Russia so easily mopping up everything she wants. I don’t know

whether the job of putting her back in her place will devolve on us when we have finished with

Germany, and if so, how anyone can decide here her place begins and ends.

I have just been thrilled reading the graphic account of the experience of the men in a submarine

which, after hours below the water being battered by depth-charges managed to rise to the surface

and struggle safely home. It would make Rupert feel proud to belong to the Navy.

Rachel’s Letters 1939

I wish I knew how fully things are being reported out there – I often think of sending papers and

things and then decide that you are sure to have had the same news.

I am very well. Love to you all, Rachel

Rachel’s Letters 1939

Bath

Oct 16th, 1939

Dear Family,

I have just returned to Bath after a week with Susie’s family in Cornwall. I shall only be here for a

couple of days while Betty and co are here and shall then go up to London for a few days to fix up

some business. Betty sails in the Orion on 21st. I shall then go back to Cornwall for a few weeks – it

gives me something definite to do and sets Susie free to go to Portsmouth to Arthur. Four days after

she got there last time he was sent away, so she came back. He has not gone to sea permanently yet

though. It was quite pleasant in Bude, but a bit bleak and wind-swept (‘bracing’, people here call it).

It is certainly much pleasanter in the summer, but it is still very jolly walking along the cliffs on the

springy turf.

I was sorry to leave Bath. It is a picture just now with the trees turning yellow, and crimson Virginia

creeper. All the buildings in bath are built of local stone of a pretty creamy grey. It is very soft when

quarried and can be cut with a saw, but after exposure to air, hardens and becomes very durable.

I have really been extraordinarily fortunate to have been able to join up with the girls and Miss

Stratton during this last month. We have really had a happy time in spite of everything. The Evans

girls have bought a tiny radio, which has been a great joy to us all. They heard today that they are

not allowed to take it out with them, so they have offered it to me to use while I am here, and I shall

take it out to them when I come.

Good London theatrical companies are now touring the provincial towns. We went the other day to

see “French without Tears” – a most amusing show. They put it on from 7 till 10, and it was crowded

and enthusiastically received. It is the only time we have been out at night. It is often not worth the

trouble of stumbling home in the black out, though it makes all the difference now we are allowed

to flash a torch on the pavement.

The loss of the Royal Oak on Saturday was a severe blow. It does seem dreadful that such a small

proportion of the crew should have been able to be saved. We haven’t heard any details yet.

Today several German planes got through and raided Edinburgh, but they were driven off and some

brought down. They dropped bombs but apparently didn’t hit anything.

Oct 21st, London

I have just been saying goodbye to Betty and the girls and Miss Stratton. They have gone in the

‘Orion’ with a convoy, route unknown. Visitors were not allowed to go down to Tilbury, and the boat

trains from St Pancreas were very crowded with the passengers for several ships.

Then I went on with Helen Taylor to a matinee of a new play of Priestley’s, “Music by Night” – a

strange thing – a dozen people are listening to a new concert being played by the composers, and

the effect of their music on their various minds is shown in a series of little scenes. The spotlight

picks out each in turn, and they act out their thoughts. It was very well done.

One of my reasons for coming to London was to interview the powers that be at Bedford College

(the Women’s College of the London University) where they have an organisation for enrolling

graduates for specialised work in the present emergency. It seemed to be very well run by an

extremely nice lot of women, and they accepted my application, but told me just what I expected to

hear, that until things begin to happen there is no medical work for anybody. Eventually they

Rachel’s Letters 1939

suppose we shall all be needed, but it may not be for months or even years or perhaps not at all – or

it might be tomorrow.

I wandered into Madame Tussaud's the other day and remained completely fascinated for 4 hours.

The models are marvelously realistic, and cleverly grouped in very natural attitudes. I was amazed at

the amount of expression they had managed to put into their waxen faces.

The leaves are falling fast now, and in some places the trees are almost bare. There is no doubt it

must be thrilling to live in a country which is constantly changing its appearance! English people in

Australia must find our seasons very monotonous.

London is looking fascinating just now with a haze of light fog softening everything. I am just

beginning to feel its charm – at first it just struck me as very large and rather dingy.

There is a sharp nip in the air which makes me wonder what I’ll do in the winter, as I find it distinctly

cold already. The clothes I was counting on for the winter feel like muslin when I get out in the wind!

One advantage is that you can walk for miles and feel as if you’re walking on air.

It is not nearly so hazardous going about at night now. The buses have blue lights showing their

destination and faint lights inside as well. The traffic lights are a shade brighter and cars also are

allowed a little more. Altogether, there is a faint glow by which you can just distinguish solid objects.

I went to Putney to see the Roberts today. Gwendoline had been on duty all night at an ARP station

and does her ordinary job in the daytime as well.

London is pretty dead. The shops are almost empty of people, all the museums and galleries closed

and practically no theatre except a few musical comedies; not more than half a dozen cinemas are

open.

Much love to you all. Rachel

Rachel’s Letters 1939

Bude

Cornwall

Nov 26th, 1939

Dear Family

There is not much news, but it is time I started another scribble to you.

Last Sunday we returned to winter time (putting back the clock 1hr), the summer time having been

kept on longer than usual. So now we arrange the black-out curtains over the windows at 4.30, just

before we sit down to afternoon tea! It makes the day very short, but it is nice to get up in daylight,

which we haven’t been able to do for some weeks.

This has been a very bad week for shipping. I imagine that these mines are probably Hitler’s secret

weapon which he has been threatening us with and which cannot be used against him in return.

They call them “magnetic mines”, and they are apparently worked by a little magnetic needle falling

into place and setting them off when the hull of a ship passes close to them. They are laid by planes

landing on the sea, or by parachute from the air and, unfortunately, it is not possible to sweep for

them as for other mines. I have no doubt we’ll evolve some way of dealing with them, but

meanwhile they are doing terrible damage. Our retaliation of capturing German exports on the seas

seems to be causing unfavourable repercussions among the neutral countries.

According to people here, Holland had a very narrow escape from invasion on Nov 11th. All plans

were made but Hitler’s generals were against it, and he changed at the last minute.

Susie came back a few days ago and I unfortunately had to hand Rosemary back to her with a nasty

attack of bronchitis. She has been in bed for about a week but is on the mend now.

I quite enjoyed being domesticated again. I did the cooking while the little maid took charge of Rose

Patricia, who is rather delicate and usually has her own nursery governess to look after her.

Groceries seem to be very cheap in comparison with ours, and meat very expensive. (I ordered 3

small sheep’s livers the other day, thinking I was getting a cheap dinner, and found they were 2/6

each). I am getting used to using margarine for cooking and find it quite good. A children’s specialist

told Susie always to use it for cooking as cooked vegetable fats are more digestible than animal.

I have just been listening to Mr Chamberlain’s first wireless speech since the outbreak of war – very

calm and confident – it gives one encouragement! He puts everything very clearly and never says a

word too much.

We have been having wet squally weather with high winds and the seas, a dirty greeny-grey, are

crashing on the rocks below the house. One can’t help thinking all the time what it must be like to be

suddenly thrown into such a sea! There is much rescue work going on on the East coast but here it is

very quiet.

Here we must feel nearly as remote as you do out there! It seems strange to be just carrying on with

an almost normal life, knowing that at any minute Hell may break loose or that – equally likely –

nothing may happen at all.

Do you get the speeches reported in your papers? Lord Halifax made a very fine one a few weeks

ago. I hope you are able to see “Punch” sometimes. It gives a splendid picture of all the funny little

details of life over here just now.

Much love to you all, Rachel

Rachel’s Letters 1939

Bude, Cornwall

Dec 5th, 1939

Dear Family

The house seems strangely quiet and rather creepy, as the family all departed for home 3 days ago.

There was a further week’s rent paid on the house, so I decided, for reasons of economy, to stay on

in it for a little while. The weather is very wild – not cold, but wet windy, so I am glad to be able to sit

by the fire and not to be travelling about just now. I am only using the kitchen, which has a

permanent anthracite stove for heating the water in it and is very cosy. I have decided that with our

modern small tiled hygienic kitchens we lose a very pleasant and comfortable room from the house!

It has been an opportunity to get quite a lot of sewing and odd jobs done, as it has been a busy time

up till now.

Susie is going to stay on in her own home now and is sending Rosemary back to the school she has

been attending in Bude as a boarder. She is a nice child, and I think will turn out well, but I have

never met a child more in need of boarding school, so the present trouble may have a good result

for her.

I am always seeing strange and fascinating birds and wish I had someone to tell me what they are.

There seem to be dozens of different sorts of gulls. Along the edge of the canal just outside the

house they sit in long rows, and some of them are, literally, as big as fowls.

Dec 10th Gastard House, Horsham, Wiltshire

I am now spending a week with Cousin Jean Fowler. She is well but has a good deal aged, and I think

she feels the big place something of a burden to run now. She no longer rides a bicycle but has a nice

little Vauxall car. She did have 3 evacuated teachers billeted here, but they now have a cottage of

their own in the village, so she has the house to herself again. Cousin Elfrida, a sister who lives in

Oxford is staying here too. I find she is an accomplished French scholar, so she is very kindly doing

some reading with me and helping me a lot.

The winter scenery has great charm. The bare trees with their tracery of twigs against the grey sky,

look like an etching. The field are very wet to walk in, and the grass lush and vividly green. I should

have thought the heavy frosts would have burnt it off, but they haven’t so far. The houses about

here are all of grey stone – as grey as the present sky. They are steeply gabled and roofed with thin

stones laid like slates.

On the way here from Bude I spent 2 days at Dawlish in order to see the old Misses Cooke from

Hunters Hill. Dawlish is a pretty little town on the south coast of Devon – about 10 miles from

Exeter. The cliffs there are bright red – a great contrast from the grey Cornish coast I have just left.

The Cookes were just the same as I remember them – Miss May very large, talkative and important

and Miss Daisy freckled and wholesome looking, quieter and forever dancing devoted attendance on

her sister. They are obviously very badly off but are cheerful and full of interest in everything.

They produced many reminiscences about our early days – such as when we were at Kiama and

Howard was about 2 – he said one day “I want to kiss you, Miss Cooke”. “Not with that dirty face”

she said, “Go and wash it”. He came back in a few minutes, his face slightly cleaner but smelling to

high heaven. “Where did you wash your face?”, “Oh in the fowls’ dish!” (Howard won’t appreciate

that story)

Rachel’s Letters 1939

They found me some lodgings where I had bed, breakfast and supper, and I had lunch with them.

They still keep in touch with many of the Hunter’s Hill people and write to Aunt Pollie about once a

month.

I have heard nothing about my hospital, so am just filling in time. I am drifting back towards London

now.

Susie wanted me to go there for Christmas but I decided not to, as they have had a good dose of me

lately and, having been separated for so long, I thought the family would like to be together on their

own.

I didn’t know quite where to go, and didn’t want to be alone in my not-very-exciting London lodgings

so I have booked a room for a week at a hotel in Windsor, where I lunched one day with Miss

Segaert (it is run by a friend of hers). It is rather more expensive than the type of place I usually

patronise but is very nice and I thought a little extravagance was justified as I have been very careful

lately. I may go up to London on Xmas day to a function they are holding at the Overseas Club but

am not sure if it would be worthwhile.

Much love to you all, Rachel

Rachel’s Letters 1939

40 Queensborough Tce.

Bayswater W2

Dec 23rd, 1939

Dear Family,

I have had a few days in London shopping, re-packing etc, and go to Windsor this afternoon It has

been foggy for several days. Not a bad fog, they tell me, but it seems thick to breathe, and you can

taste it. Even inside the rooms there is a yellow haze, and the sun, when it manages to show itself at

all, is like a blood red orange.

London grows more normal every time I see it. All the tube stations are opened again now, and they

have evolved a modified form of street lighting – just a faint glow like pale moonlight. It is just

enough to see solid objects and avoid them. They have started in Piccadilly Circus, and hope to have

it everywhere before long. I discovered the first morning I went out, that I was about the only person

in London carrying a gas-mask, so now I leave mine at home too – they are nasty awkward things to

carry.

The barrage balloons still keep guard overhead and give a faint sense of security. They are supposed

to make it difficult for planes to swoop down on an objective and drop bombs with accuracy – of

course it is death for a plane to touch one or any of the cables attached to it. They are bright silver,

and when the sun is out, look so pretty, and at sunset they become luminous with pink and gold, and

shine long after the sun has left the earth.

All the worth-while statues have been covered with sandbags (I enclose a picture of one) causing

acid comments to be chalked on walls “Sandbag worker’s homes not statues”!

Most noticeable are all the empty houses, many of them with windows boarded up, have evidently

been left for the duration. In others, through blank windows, you can see sheeted furniture.

Many of the business houses though are taking up their quarters in London again, as trying to carry

on business in the country has proved so costly and difficult, and the absence of air-raids has given

them confidence to return. I expect they’ll keep a funk-hole in the country to retire to though.

My landlady attended a police-court last week with 50 other boarding-house keepers who were

summonsed for not paying their rent. They have all made a compact together not to pay, as of

course, their receipts have dropped to almost nothing. I don’t know how it will all be adjusted.

The cold has been pretty severe. Through my window I have been watching the frost crystallising on

the twigs of the tree outside, and although it is midday and should be the warmest part of the day, it

is getting whiter every minute. I find I am not feeling the cold as much now as I did in the autumn.

Whether the intense cold is more bracing, or due to the fact I am wearing more clothes, or that the

calcium lactate I am taking for chilblains has improved my circulation, I don’t know, but I am quite

enjoying it.

I enjoyed my stay at Gastard with Cousin Jean. Under her brusque manner, she has a very kind heart,

and she was very good to me. There was only one great drawback – she would take me for drives,

and she drives at anything up to 50 miles an hour on the wrong side of the road! When, after several

hair-breath escapes (for which she blamed the other man for going too fast) I murmured “Well. You

were on his side of the road”, she replied “Oh yes, I find it easier to watch the right hand kerb than

the left!”

Rachel’s Letters 1939

She had an extremely nice youngster staying there, a great nephew called Robin Barbour – a Scotch

boy who has just left Harrow Rugby and gone to Oxford. I was struck again, as I remember being

struck last time I was here before, by the precocity of the English schoolboy. Although they give a

respectful hearing to their elders, they take an equal part in the conversation with older men and

seem to have such a wide knowledge and mature judgement and any amount of confidence.

I had dinner with Helen Taylor at her lodgings one night. When I return to London, I think I'll move

there for a while, - at least till Helen leaves. She is working very hard for another attempt for her

FRCP in January and when that is over her father wants her to fly home.

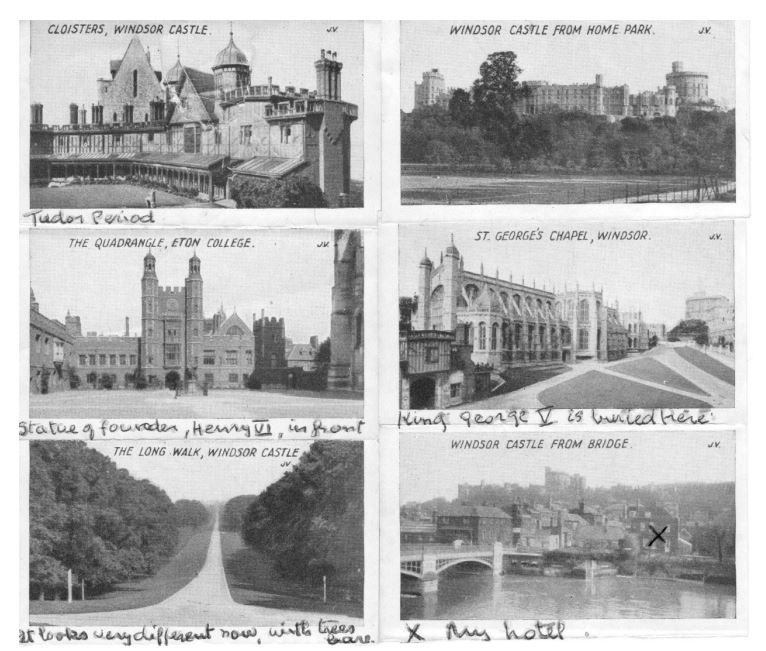

Dec 28th The Old House Hotel, Windsor

This is a charming old house, built and lived in by Christopher Wren in 1670, attractively furnished,

and very well run. The food is marvellous, and the service quite exceptional. It is not very full, but

there seem to be some quite agreeable and friendly people. There is one very charming couple, the

husband Czech and the wife Hungarian. The place is owned and run by an old Etonian, and many

Eton parents come here in term time.

I had quite a pleasant Xmas. In the morning, I went to church in St Georges Chapel in Windsor Castle.

(It is the only part of the castle one is allowed to go into now). It is a beautiful chapel, all cream

stone, beautifully carved inside, and with many crests and coats of arms picked out in colour. I

couldn’t hear a word of the service, which all took place in the choir behind one of the heavy screens

between the choir and the nave, which I hate so; but the singing of the little boys was beautiful.

I went up to London in the afternoon to a dinner dance held at the Overseas Club. They specially

cater for strays like myself, and this was particularly to entertain some of the Canadian soldiers. It

was quite fun. They had big tables, and everyone was friendly and cheerful. The Canadians were

mostly rather shy, and, as one of them confided in me, afraid of not doing the right thing. After

dinner they had plenty of dances of the ‘Jolly Miller’ kind to mix everyone up, and it all went quite

well. I had taken a room at the club for the night, so tumbled into a most comfortable bed, slept late

in the morning and returned here the next day. It had been a very foggy night and many people

were very late for the dinner, and about a dozen couldn’t get there at all. There was an Indian Naval

cadet there and 2 Indian flying men. The latter were most striking-looking. Tall well-built and

aristocratic-looking, they wore blue air-force uniforms and turbans. They had good manners and one

made an excellent speech.

On Boxing Night, they held a dinner-dance here, and about 150 people turned up. Some girls were

dancing in uniform, but there were lots of pretty dresses too, and it was very gay. The proprietor, Mr

Black, asked if I’d like to join their party, so I did for a while and enjoyed it.

This hotel is situated right on the bank of the Thames. The large glass windows surrounding the

dining room, which looks on to it are all boarded up against bombs, so the lovely view I remembered

when I lunched here in June has gone, but the river looks pretty grey and cold this weather anyway.

The castle is an amazing pile of masonry, towering over the town, covering acres of ground, and

comprising dozens of buildings of various periods. It is most imposing. I am sorry it is not possible to

go and have a look at it.

The town runs in a long street from the Castle and Park at one end, on a hill, to Eton College on the

flat by the river at the other end. That also is an amazing size – dozens of beautiful buildings and

lovely park=like grounds. The road runs right through the middle of it. I don’t know whether it would

be possible to see over it in holiday time, but I hope so.

Rachel’s Letters 1939

This morning it started to snow just after breakfast and has never stopped all day. It is fascinating to

watch it falling, and everything being transformed. I went for a long walk in the park while it was all

fresh and beautiful. This afternoon the streets were all getting sloppy and dirty and men were

scraping it off the paths and sanding the roads. It is not very cold.

The war drags on! The last 2 weeks have been memorable ones for the Navy, with the ‘Graf Spee’

episode and the exploits of the ‘Salmon’ and other submarines.

Finland seems to be achieving the impossible! It seems now as if she might be able to hold out till

the spring, while the weather is in her favour. After that I suppose it depends on what support she

has been able to gather to herself in the meantime. Good luck to her!

Rationing of butter, bacon and sugar starts next week. I don’t think it will be any great hardship to

anyone.

Much love to you all, and may we see better days in 1940!

Rachel